The challenge of securing colours and colour combinations as trademarks

Although not impossible, it can be difficult to protect a colour or combination of colours as a trademark. Novagraaf’s Timo Buijs examines the function of colours in trademark law and the challenges of registering colours and combinations of colours as trademarks in light of a recent EU ruling.

According to a number of rulings by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), it is necessary to prevent certain colours from being monopolised by companies, for reasons of general interest and free competition. However, a colour or combination of colours can be registered as a trademark when it acquires distinctiveness.

Acquired distinctiveness

Practice shows that a colour can only obtain trademark protection when it has acquired distinctiveness. In other words, if the relevant public has started to recognise the trademark for certain goods or services as originating from a certain company, as a consequence of the use of the trademark. This means that the goods or services for which trademark protection has been sought (in this case a colour or combination of colours), can be distinguished from the goods or services of other companies by the relevant public, since the certain colour or combination of colours has been used in a intensive way and/or for an extensive amount of time.

Single colours

The CJEU ruled in the Libertel judgement that a single colour can be registered as a trademark, provided that it can be displayed graphically in a clear and precise manner. This last condition will not be fulfilled by simply reproducing the colour on paper. By also mentioning the internationally recognised colour code in combination with a colour sample, the requirement will be met. From October 1 2017, the requirement of graphical representation is no longer needed in the European Union. The same applies to the Benelux as of January 1 2019. However, this change is not important for the registration of colour marks. Applications for registration of colour marks have to meet the new requirement of being able to be represented in a ‘clear and precise manner’. Applications for registration of colour marks must also contain the colour code and/or a colour sample in order to be registered as a trademark. In addition, acquired distinctiveness has to be demonstrated. Well-known registered trademarks consisting of a single colour include 'magenta' for T-mobile, Zwitsal-yellow and purple for the chocolate bars of Milka.

Combinations of colours

In addition to a single colour, a combination of colours can be registered as a trademark. Specific conditions also apply to such trademarks.

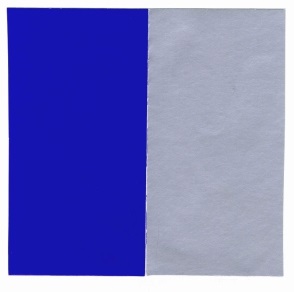

According to CJEU case law, a combination of colours can be registered as a trademark, only if the application for registration includes a ‘systematic arrangement associating the colours concerned in a predetermined and uniform way’. In other words, if the description of the application for registration only consists of two colours that can be used in all conceivable forms, the application will be refused. It is required to clearly describe how the combination of colours will be used on the goods or services applied for. This ruling ensured that many registrations of (well-known) combinations of colours are no longer seen as valid trademarks. For instance, the following combination of colours of brand owner Red Bull GmbH was annulled by the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) in 2015, which was later confirmed by the EU General Court:

In another judgement of 25 October, the CJEU ruled in line with the Red Bull case. The main question in this case was whether the following sign, consisting of ‘blended shades of green' for wind energy converters and components can be registered as a trademark:

Enercon filed an application for registration of the above-mentioned sign as an EU colour mark. A colour code was submitted with the application, showing that Enercon had the intention to register the sign as a colour mark. A third party filed an application for a declaration of invalidity against the EU trademark, which was assigned by the EUIPO. The Office argued that the trademark defines the way in which the registered colours could be applied to a wind turbine tower and has no distinctiveness as a colour mark.

In its appeal, Enercon stated that the trademark should not have been registered as a colour mark, but as a figurative mark and it was not possible to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness of the combination of colours. The Board of Appeal of the EUIPO honoured this defence. However, on appeal, both the EU General Court and the CJEU claimed that the mark at issue was indeed a colour mark, which lacked any distinctiveness.

Strict requirements

Colours and combinations of colours are used by many companies as a sign to distinguish their goods or services. However, when considering applying to obtain trademark protection of a colour or combination of colours, be aware that strict requirements apply. Demonstrating acquired distinctiveness is almost always required, while the concerned colour or combination of colours must be described in a clear and precise manner.

The CJEU’s recent judgment emphasises once again that colour marks do not easily meet the condition of distinctiveness, and that a well-considered strategy must be used to acquire distinctiveness for the goods and services applied for.

For additional advice on registering a colour as a trademark, speak to your Novagraaf attorney or contact us below.

Timo Buijs is based in Novagraaf's Competence Centre in Amsterdam.