Prior art searching: Is your goal patentability or freedom to operate?

When carrying out prior art searches, it’s important not to confuse the objective of patentability with that of freedom to operate. Vincent Robert explains the distinction.

At Novagraaf, we consider it important to clearly identify the needs of our customers in order to offer them the most appropriate service. For this, discussions with the client, whether face-to-face or remotely, are essential because they allow us to resolve certain ambiguities associated with patents and product launches.

For example, when businesses develop a new product, they frequently ask their advisers to undertake a prior art search of existing patents. However, there can be a misconception about the desired objective for such a search. Indeed, the confusion between freedom to operate and patentability often appears in our discussions.

In some cases, the main goal of the customer is to ensure that they are free to bring their product to the market without running the risk of infringing competitor patents. The question of patentability – “Can I obtain protection for my invention?" – is only secondary, therefore. The main objective being to establish freedom to operate.

In other cases, the main objective of a client is to determine whether they can protect their invention with a patent and thus obtain a monopoly on the exploitation of that invention. Here, the main objective is that of patentability.

The difference between patentability and freedom to operate

Where the main objective is patentability, it is not always well understood that, while you can validly patent a technical solution, it may still not be possible to place it freely on the market. The will most often arise in the case of improvements made to a known device, for example.

Let's

Let's  take as an example, the case of a company ‘W’ that has a patent (B1) in force protecting the principle of a barbecue in the shape of a sphere cut in half, the upper part of which forms a removable cover with a handle (see left).

take as an example, the case of a company ‘W’ that has a patent (B1) in force protecting the principle of a barbecue in the shape of a sphere cut in half, the upper part of which forms a removable cover with a handle (see left).

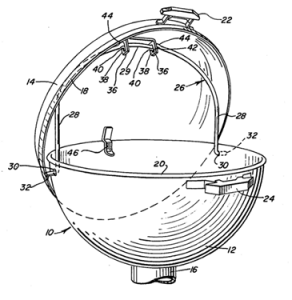

Now imagine that our client, company X has developed a patentable improvement (B2) to this barbecue model; for example, in the form of a hinge that connects the lid to the bowl for easier handling (see right).

Depending on the objectives for the prior art search, the outcome will be different:

- Patentability objective: The research carried out leads to a positive opinion. It is possible for company X to obtain a valid B2 patent protecting the hinge mechanism.

- Freedom-to-operate objective: The research carried out results in a negative opinion. Company X's marketing of a barbecue equipped with the hinge mechanism infringes company W’s B1 patent. The holder of the B1 patent is entitled to prohibit the hinged barbecue from being marketed.

To analyse a new product, therefore, it is not enough to verify that it is patentable, it is also necessary to ensure that it is not infringing a competing patent.

In addition, depending on the desired objective, the search for prior art will not be carried out in the same way. For freedom-to-operate searches, we will mainly focus on the patents in force while, for patentability searches, any public document can constitute valid prior art, including a patent that is no longer in force.

The Novagraaf teams are well aware of these distinctions and can support you throughout the development of your products, enabling you to act freely and in a position of strength in the market. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact your Novagraaf attorney, or contact us below.

Vincent Robert is Director of the Mechanical Department and a Patent Attorney at Novagraaf in France.