Trademark artwork: How to use works of art in branding

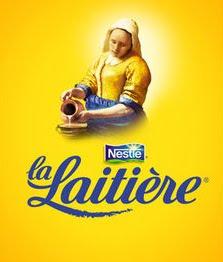

Have you ever thought about using a well-known painting or work of art as a trademark? It is a strategy that has proved successful in the past, as illustrated by Nestlé’s adoption of the Johannes Vermeer painting Milkmaid. However, there are a number of pitfalls that must first be identified and overcome, as Volha Parfenchyk explains.

Trademark registration of works belonging to the world cultural heritage has become a sought-after strategy for companies seeking to distinguish and advertise their products to the public. Nestlé’s registration of the Johannes Vermeer painting Milkmaid for its range of milk-based desserts (see image, right) is perhaps one of the most successful marketing strategies involving the use of a well-known artwork. But to what extent is this strategy fool-proof and how can you overcome the inherent risks?

Trademark registration of works belonging to the world cultural heritage has become a sought-after strategy for companies seeking to distinguish and advertise their products to the public. Nestlé’s registration of the Johannes Vermeer painting Milkmaid for its range of milk-based desserts (see image, right) is perhaps one of the most successful marketing strategies involving the use of a well-known artwork. But to what extent is this strategy fool-proof and how can you overcome the inherent risks?

Art as a trademark: What does the law say?

The registration of a well-known work of art (such as a painting or a sculpture) as a trademark is not explicitly forbidden by EU law, as long as this work rests in public domain. In other words, to freely (re)use any artistic work for your trademark, its copyright must have already elapsed. In Europe, the duration of copyright on artworks is generally 70 years after the death of the author. After that any company is in principle free to (re)use these artworks for any goals, including using them as a constitutive element of a trademark.

Possible pitfalls

Of course, the practice is more complicated than this might sound. Companies wishing to register a well-known piece of art as their trademark should be wary of two main pitfalls:

Firstly, the trademark office may consider such a trademark to be ‘devoid of distinctive character’ and therefore refuse the trademark application. Lack of distinctiveness is one of the main absolute grounds of refusal of a trademark application under article 7 of the EU Trademark Directive (EUTMD). Trademark applications that have worldwide known objects of arts as their constituent element are susceptible to refusal because they are well-known to the public and are often used in advertising.

Over the years, the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) has refused a number of trademark applications that involve well-known works of art due to their lack of distinctiveness. A well-known example is the 1997 Mona Lisa case, in which the German Federal Patent Court ruled that the trademark involving Mona Lisa lacked distinctiveness because it has been used multiple times by other parties in advertising. In other words, consumers would fail to associate the trademark with a particular company. A similar 2015 case revolved around Rembrandt’s painting Night Watch in which the Court of Appeal of the Hague similarly ruled that the trademark lacked distinctiveness and refused its registration.

Secondly, a trademark application may be rejected on the grounds that it violates public policy and morality. In other words, in cases like this not the trademark as such that is seen as offensive, but rather that the registration of a trademark is seen by the trademark office as contradicting public policy and morality. In a widely discussed case around the works of the Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland the Court of Justice of the European Free Trade Association States ruled, for example, that certain works of art enjoy a “particular status as prominent parts of a nation’s cultural heritage, an emblem of sovereignty or of the nation’s foundations and values”. The registration of these artworks could be seen by the relevant public as offensive and contradicting the accepted principles of morality.

How to overcome these pitfalls

These complications, as such, do not prevent companies from successfully registering a trademark involving a well-known work of art, even if the trademark application has been initially refused.

National and EU trademark authorities can vary in the ways in which they interpret and apply the provisions of EU trademark law and this can often lead to different – and at times contradictory – outcomes. The registration of a trademark involving Rembrandt's painting Night Watch provides a pertinent example. While the Dutch court refused the application due to the lack of the trademark distinctiveness, the EUIPO found the trademark to be distinctive and ruled in favour of the applicant.

In addition, trademark applicants can seek to rely on the ‘acquired distinctiveness’ of the trademark to overcome a descriptiveness/non-distinctive trademark refusal. Acquired distinctiveness means that the consumer has come to perceive the mark in question as a trademark, due to its long and well-established use. Therefore, if the trademark application based on a well-known work of art has been refused by the trademark authority as lacking inherent distinctiveness, the company can try to prove that such distinctiveness has been acquired in the course of practice. (For further advice here, read our article on preparing evidence of trademark use.)

The refusal of the trademark application based on the violation of public policy and morality is more difficult to tackle. Such refusals cannot be opposed by appealing to the ‘acquired distinctiveness’ of the trademark and, therefore, are more difficult to circumvent. Luckily, the courts are quite reluctant to appeal to this ground. There have been only a few cases (of which Vigeland is one) in which the courts actually denied registration for artworks based on the grounds of public policy and morality.

Art as a trademark: Finding a way forward

The registration of a trademark involving a well-known work of art, be it a painting or a sculpture, is certainly not without pitfalls. However, these pitfalls do not constitute insurmountable barriers. Being aware of these pitfalls, as well as designing a strategy for avoiding and overcoming them, can pave the ground for a positive decision by the trademark office.

For more information about (the registrability of) trademarks, speak to your Novagraaf attorney or contact us below.

Volha Parfenchyk is Novagraaf’s Knowledge Manager. She is based in Amsterdam.