Threats with a smile: The cease-and-desist letter in a time of social media

Cease-and-desist letters aren't usually associated with a humorous tone, but levity can sometimes be more effective than dry threats.

On 23 September 2020, Bill Murray was sent a cease-and-desist letter by Peter Paterno of the law firm King, Holmes, Paterno and Soriano LLP, representing the rock band the Doobie Brothers. The letter called out William Murray Golf, the apparel brand set up by Murray and his five brothers (in a nod to one of his career-defining roles as a deranged gamekeeper in Caddyshack), for using the Doobie Brothers’ song Listen to the Music, among others, without permission. Given the dry, even stodgy phrasing one might expect from legal correspondence, Paterno’s letter is worth reading in full as a daring, tongue-in-cheek exercise in dry humour. Where he would be expected to specify the law that Murray is infringing, Paterno writes instead:

"This is the part where I’m supposed to cite the United States Copyright Act, excoriate you for not complying with some subparagraph that I’m too lazy to look up and threaten you with eternal damnation for doing so. But you already earned that with those Garfield movies. And you already know you can’t use music in ads without paying for it."

Clearly, the letter is meant not just to alert Murray to an infringement, but also to elicit a few good-natured laughs. Paterno’s letter reads as if it were written for Murray to recite in the deadpan style that his fans have come to know over the course of his career in film. And therein lies the savvy of Paterno’s letter. Not only did it move to protect the Doobie Brothers’ rights, it also tipped the hat to Murray’s mastery of comic understatement, thereby dulling the edge that comes with a threat of legal action, and positioning it well to generate a lot of positive attention, if it went public – which, of course it did. Eriq Gardner of The Hollywood Reporter posted a copy of the letter to Twitter, where, as of writing, it has been retweeted more than 11,000 times and received almost 50,000 likes. The story has also been picked up in the New York Times, Reuters, Fortune, the Huffington Post, and the New York Daily News, among others, from where it has been shared on any one of the many social media platforms for people to laugh along with such a letter and to marvel at its brio.

The letter also elicited a response in a similar tone from the firm representing William Murray Golf, although it seemed to be only offering golf shirts and song puns given that the Doobie Brothers "were not harmed under these circumstances".

Going viral for the right reasons

This isn’t the first time in the history of IP law that a cease-and-desist letter has reached a wider audience than the infringing party, nor that the authors of such letters have written them with the greater public in mind. In August 2017, Netflix sent out a cease-and-desist letter to a pop-up bar called 'The Upside-Down' in Chicago themed around its hit series Stranger Things. The letter was keyed perfectly to the addressees: it was peppered with knowing, humorous references to characters in the show, thus establishing a measure of complicity between Netflix and the owners of the pop-up bar. Nevertheless it made clear that Netflix was serious about defending its rights: The bar owners had to clear up the infringement, or else Netflix would have to “call your mom”. Of course, the letter went viral and was positively received, being described as “hilarious” in the Sydney Morning Herald, “cool” in Fortune, “cheeky” in the Chicago Tribune, and “epic” on boredpanda.com.

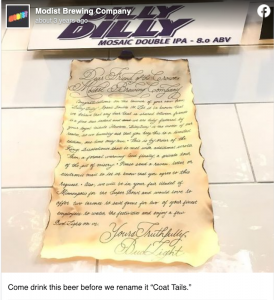

Then, in December 2017, Anheuser-Busch, the brewery behind Bud Light, turned the cease-and-desist letter into a performance when it sent a man dressed as a town crier from the Middle Ages to Minneapolis-based Modist Brewing Company, informing it via scroll (see right) that its Dilly Dilly brand infringed Anheuser-Busch’s trademark rights. It added that this had to be resolved – lest Modist Brewing be led on a private tour of the “Pit of Misery” – before, in an open-handed gesture, inviting two of its employees to the Super Bowl. The performance was recorded and posted online, where it has received 610,000 views on the Facebook page of the Modist Brewing Company alone.

Then, in December 2017, Anheuser-Busch, the brewery behind Bud Light, turned the cease-and-desist letter into a performance when it sent a man dressed as a town crier from the Middle Ages to Minneapolis-based Modist Brewing Company, informing it via scroll (see right) that its Dilly Dilly brand infringed Anheuser-Busch’s trademark rights. It added that this had to be resolved – lest Modist Brewing be led on a private tour of the “Pit of Misery” – before, in an open-handed gesture, inviting two of its employees to the Super Bowl. The performance was recorded and posted online, where it has received 610,000 views on the Facebook page of the Modist Brewing Company alone.

How you protect your brand reflects your brand

Of course, three funny letters do not a trend make, and one would be hard-pressed to make the case that we are entering into a golden age of the cease-and-desist letter as popular entertainment. Thousands of such letters must be issued every day around the world, yet the number of them that make such a splash in any given year can be counted with the fingers on one hand. Nevertheless, the three cases described above can provide some useful insights into the connections between brand promotion and brand protection strategies, specifically in a consumer environment in which social media can drive brand sentiment on a scale and at a speed that can be difficult for a business to control.

When you have a brand that enjoys special prominence in the public eye (Netflix/Stranger Things, Bud Light) that is based on a carefully cultivated persona (the cool, retro-chic show that provides a nostalgia hit to Generation X and tells an awesome story as well; the mainstay of good times with friends), then consumers expect that the way you promote your brand is of a piece with the persona you project. By the same token, what you do to protect your brand can quickly become an image management issue, especially when you act against a party that may not enjoy as widespread brand recognition (Danny and Doug the pop-up bar owners; the Modist Brewing Company). One can imagine that a smaller business with a devoted following can try to paint you as a bully and killjoy, for example by leaking to social media a cease-and-desist letter with the hope that the public will see it as a display of excessive force and rally to your support (see, for example, the recent dispute between tech giant Apple and small healthfood company Prepear). Such a move would be, in these cases, very un-Stranger Things or un-Bud Light, and consumer backlash could be bad for business. What the Netflix and the Bud Light cases show is that if a cease-and-desist letter is written in a way that spotlights just those aspects of a brand’s persona that consumers find attractive, it would not only reaffirm a brand owner’s rights but it could also be a good opportunity to generate positive buzz.

The Doobie Brothers-Bill Murray case also illustrates how a brand that is perhaps less well known can use the humorous cease-and-desist letter to draw attention to itself in a similarly positive and possibly profitable manner. A standard cease-and-desist letter might only go as far as its intended addressee and achieve its desired effect. But, by sending a letter that parodies Bill Murray’s comic persona and having it diffused online, the Doobie Brothers draw attention to themselves and their music. Specifically, they enter the public eye as “that band who sent out that epic takedown and whose catchy tune was in that Bill Murray advertisement”. With that new prominence, who’s to say that they might not find more opportunities to have their music featured in other advertisements, television shows, and so on?

The social media challenge

In this time of social media, image is (almost) everything, and how you curate that image, or the persona you present to the world, can make a difference to how others interact with you. This is perfectly illustrated by the recent Dolly Parton Challenge, aka the LinkedIn-Facebook-Instagram-Tinder game (see right). This is just as much the case for brands, and especially so for brands perceived by the public as having a specific persona.

In this time of social media, image is (almost) everything, and how you curate that image, or the persona you present to the world, can make a difference to how others interact with you. This is perfectly illustrated by the recent Dolly Parton Challenge, aka the LinkedIn-Facebook-Instagram-Tinder game (see right). This is just as much the case for brands, and especially so for brands perceived by the public as having a specific persona.

The rise of social media has also made the favour of the public more fickle. A negatively perceived action can quickly and widely hurt a brand’s standing and impact the bottom line, but a gesture that reinforces a brand’s favourable image can strengthen its hold on the public imagination and even expand it. This can only be good for business. Put differently, this might ultimately be the force behind the emergence of the funny cease-and-desist letter in the age of social media, the hope of hearing a resounding “Yes!” in response to Russell Crowe’s question in Gladiator:

Are you not entertained?