Success for Louis Vuitton in pattern trademark dispute

The General Court of the EU has annulled an earlier ruling by the Board of Appeal that found Louis Vuitton’s ‘Damier Azur’ trademark pattern to be invalid. But, the Court did not yet answer the all-important question of whether the evidence supported the company’s argument that the pattern had acquired distinctive character through use.

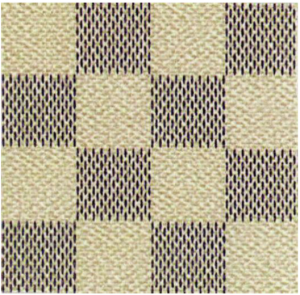

Louis Vuitton obtained an international trademark for its Damier Azur chequerboard pattern, as used on luxury leather goods, in November 2008. The trademark (pictured below right) was registered in Class 18 covering luggage, bags and other leather goods.

At the end of 2016, EUIPO’s Cancellation Division ruled on a third party's application for a declaration of invalidity on that mark. It agreed with the applicant’s argument that the trademark was invalid, based on Article 52(1) and Article 7(1)(b) of the EU Trademark Regulation (EUTMR). It also rejected Louis Vuitton’s argument that the mark had acquired distinctiveness through use in line with Article 7(3) EUTMR.

The ruling by the General Court

Louis Vuitton unsuccessfully appealed the ruling to EUIPO’s Second Board of Appeal. When that was rejected, the matter was further appealed to the General Court of the EU. During the appeal Louis Vuitton put forward two arguments:

- (1) That there had been an incorrect assessment by the Board of Appeal of the inherent distinctive character of the Damier Azur mark, since the Board had relied on alleged ‘well-known facts’ to supplement the arguments presented by the applicant for a declaration of invalidity; and

- (2) That the Board of Appeal erred in its assessment of the acquired distinctiveness of the mark through use.

The question of ‘well-known facts'

Established case law defines well-known facts as facts that are likely to be known by anyone or may be picked up from 'generally accessible sources'. Where bodies of EUIPO decide to take account of well-known facts, they are not required to establish in their decisions the accuracy of such facts.

(i) The General Court considered whether the EUIPO Boards of Appeal was entitled to base its assessment regarding lack of distinctive character of the Damier Azur mark on ‘well-known facts’.

It found that it would not be contrary to the rules on the burden of proof for the EUIPO to take the well-known facts into account. However, it is important that, when examining absolute grounds for refusal, EUIPO examiners and the EUIPO Boards of Appeal are required to examine those facts in order to determine whether the mark for which registration is sought comes within one of the absolute grounds for refusal set out in Article 7.

In addition, it is up to the party who filed the application for a declaration of invalidity to produce evidence that would call into question the validity of the mark at hand. This is because, when it comes to invalidity proceedings, EU trademarks are considered to be valid until annulled by the EUIPO following invalidity proceedings.

(ii) The General Court examined whether the fact that the mark at issue was a basic and commonplace pattern that did not depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector concerned could be regarded as a well-known fact.

Here, the General Court agreed with several facts stated in the Board of Appeal’s decision; in particular that the chequerboard pattern is a basic and commonplace figurative pattern, given it is composed of a regular succession of squares of the same size, without notable variations in relation to the conventional chequerboard pattern.

Acquired distinctiveness through use

However, in its decision concerning acquired distinctiveness through use, the General Court agreed with Louis Vuitton’s argument that the Board of Appeal had made an error of assessment regarding acquired distinctive character through use.

The Board of Appeal had divided the EU member states into three groups, and found that the evidence supplied to support the argument of acquired distinctiveness in one of those groups (group 3) to be insufficient. On this basis, it found that – individually and as a whole – the evidence had not shown the necessary acquired character.

By excluding the evidence supplied for the other groups without further assessment, the General Court considered that the Board of Appeal had file to comply with Article 59(2), EUTMR and the requirement to carry out an overall assessment of the evidence provided by Louis Vuitton.

We have written previously how the quality of evidence submitted can make or break a trademark cancellation defence (see, for example, 'Big Mac, Big Mistake'). This is particularly important in the EU, where the extent of territorial use is also considered.

As the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) made clear in its 2018 ‘KitKat’ ruling, the EUTMR does not require that the acquisition of distinctive character through use must be established by separate evidence in each individual EU member state. However, the evidence submitted must be capable of establishing such acquisition throughout the EU: “[It] is possible that, for certain goods or services, the economic operators have grouped several Member States together in the same distribution network and have treated those Member States, especially for marketing strategy purposes, as if they were one and the same national market. In such circumstances, the evidence for the use of a sign within such a cross-border market is likely to be relevant for all of the Member States concerned.”

What happens next?

Now that the General Court has decided the Board of Appeal made an error in its assessment regarding acquired distinctive character through use, it may return to the Board of Appeal for review.

For additional insight or advice on establishing acquired distinctiveness or preparing evidence of use, please speak to your Novagraaf attorney or contact us below.

Shana Rashid works at the Competence Centre of Novagraaf. She is based in Amsterdam.