The KitKat trademark ruling and the importance of proof of use

The recent ruling by the Court of Justice of the EU represents yet another knock back for Nestlé in its attempt to prove its chocolate bar shape distinctive enough to warrant trademark protection. Novagraaf’s Frouke Hekker examines what the judgment means for 3D shape marks and the requirements for proof of use in the EU.

Protecting shapes as trademarks is not as common or as simple as acquiring trademark protection for other types of signs, such as words, slogans or logos. KitKat is just one of the many high-profile examples of brands that have struggled to meet (or prove they meet) the criteria for shape marks set by trademark offices, and national and EU courts. Why has the bar been set so high?

Limits to registration

Registration limits have been imposed to prevent companies from acquiring a monopoly over technical solutions or a product’s functional characteristics. To prevent shapes and other characteristics, such as colours or sounds from being monopolised in this way, EU legislation contains three limitations. These exclude shapes and other characteristics from trademark protection, if:

- They consist of a shape or characteristic which results from the nature of the goods themselves;

- The shape or characteristic gives substantial value to the goods; or

- If the shape or characteristic is necessary to obtain a technical result.

Shapes or characteristics that are not excluded on these grounds can obtain trademark protection, but – as with trademarks in general – only if they satisfy criteria for distinctiveness. If a sign is initially unsuitable to be registered as a trademark, it could still be eligible for trademark protection by acquiring distinctiveness through use. ‘Acquired distinctiveness’ means that the trademark has been widely recognised by long-term and/ or intensive use, as a result of which the sign will function as a distinguishing sign, and thus as a trademark.

In practice, this is quite a hurdle as it can be difficult to argue that consumers recognise a shape or characteristic as a distinguishing mark of a particular undertaking. The greater the similarity of the shape or characteristic to a product’s obvious shape or characteristic, the less distinctive it will be deemed to be. Ideally, shapes or characteristics need to depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector in order to fulfil the essential function of a trademark of indicating a product’s origin.

The KitKat saga begins...

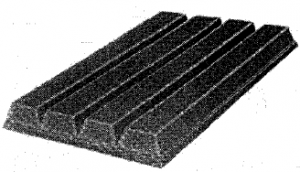

In 2002, Nestlé filed an application to register a trademark for its four-fingered KitKat bar. As the application was for a shape mark, the (word) mark KitKat was not included in the image (see left).

The application sought to register the four-fingered bar for sweets, bakery products, pastries, biscuits, cakes and waffles. Cadbury (now Mondelez UK Holdings & Services) applied for a declaration of invalidity in 2007. This declaration was dismissed by EUIPO in 2012, which held that the four-fingered bar had acquired distinctiveness through its intense and frequent use in the EU; in other words, Nestlé’s claim that the shape mark acquired distinctiveness was successful and the registration remained intact. Briefly, EUIPO’s Board of Appeal (BoA) found that:

- The surveys conducted in 10 EU member states showed sufficiently that the shape mark had acquired distinctiveness throughout the EU;

- Acquired distinctiveness was demonstrated in respect of all the goods specified in the goods and services description.

EU courts bite back...

In its December 2016 judgment, the General Court of the EU (GCEU) disagreed with the BoA findings; in particular, stating that acquired distinctiveness must be proven in all EU member states and not only in a substantial part of the territory of the EU. That ruling has now been confirmed by the Court of Justice of the EU (25 July 2018).

At the moment that Nestlé filed its application, the EU consisted of 15 member states. Therefore, the courts held that the BoA should have examined proof of use for the other member states (excluding Luxemburg).

Of particular note is the explanation in paragraphs 83–86 of the most recent ruling, which states that the regulation does not require that the acquisition of distinctive character through use must be established by separate evidence in each individual EU member state. However, the evidence submitted must be capable of establishing such acquisition throughout the EU member states. It explains that: “for certain goods or services, the economic operators have grouped several member states together in the same distribution network and have treated those member states, especially for marketing strategy purposes, as if they were one and the same national market. In such circumstances, the evidence for the use of a sign within such a cross-border market is likely to be relevant for all member states concerned.”

What happens next?

The case now returns to EUIPO, which will examine proof of use across the relevant EU member states. For its part, Nestlé has already indicated that this latest judgment is "not the end of the case" and that it believes EUIPO will side with the confectioner.

For additional insight or advice on establishing proof of use, see ‘Trademark tips: Preparing evidence of use’ or speak to your Novagraaf attorney.

Frouke Hekker works at Novagraaf’s Competence Centre. She is based in Amsterdam.